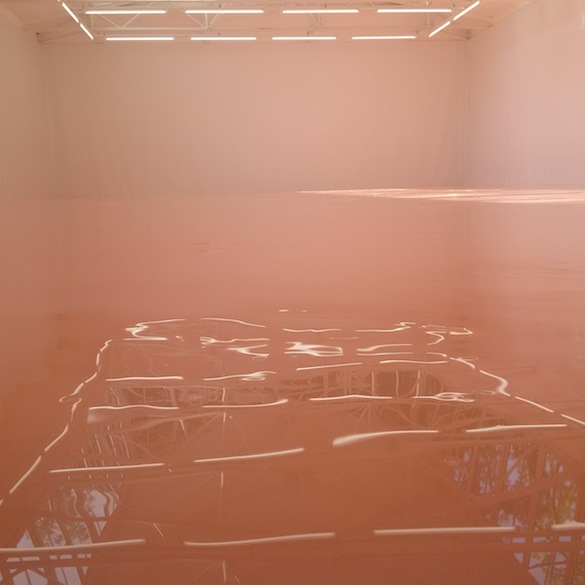

After “Our Sun”1, produced five years ago now, which was described by some2 as a piece in praise of surfaces, Pamela Rosenkranz is back in Venice with “Our Product”3, an exhibition that is nothing if not atmospheric, and yet offering a powerful image, too. Although this installation consists mainly of light, colours, sounds and smells, it is in no way a de-materialized work. The 240,000-odd litres of “product” contained in the large pool, which the Swiss pavilion’s principal room has been turned into, are impressive. This “living” monochrome, a vast expanse of a liquid with the average colour of the skin of people hailing from central Europe, is artificially rippled by small waves and complemented by an artificial noise of water digitally created in real time. It attests to the Swiss artist’s continued exploration of identity4 in a re-asserted dialectic between surface and depth, and the natural and the synthetic, here featured by simple contrasts—daylight and electric light, pink and green—but whose elements co-exist and interpenetrate in places, as if to point to the possible obsolescence of such a binary phenomenon. This is also perhaps a way of addressing the classic issues of characterizing monochromes in painting and their classification under the two great and on the face of it irreconcilable banners of autotelic materialism, that is, with an end purpose per se, and mystical spiritualism. The experience of this, here, is as physical as it is intellectual, dismissing both of these at the very least archaic considerations, the better to conjure up the twofold movement of self-dissolution and self-resistance, within and opposite the work.

“No creature lives merely under its skin; its subcutaneous organs are means of connection with what lies beyond its bodily frame[…] The career and destiny of a living being are bound up with its interchanges with its environment, not externally but in the most intimate way.”5

Our Product extends multi-media beyond the boundaries within which we usually understand it, meaning that the installation does not simply pertain to the categories we are accustomed to, no matter how open they may be—and one thus obviously thinks first and foremost of works by James Turrell (wavering between the Veil by way of the mixture of natural and artificial light, and the Ganzfeld for its immersion in colour, with the figure of the tunnel seeming to confirm the quotation), but also, for example, of Rirkrit Tiravanija’s6 Paris retrospective, where the scripts recited by lecturers and actors, or otherwise diffused in space, “incarnated” the works which were not physically on view in the show, and not forgetting Yves Klein, a recurrent reference in Rosenkranz’s work. Actually adding to the physical experience already soliciting the senses of sight, smell and hearing, and almost of touch through the immersive sensation it arouses, Our Product, by its very title, includes anyone who ventures to the heart of an all-encompassing concept. Playing with the ambiguity sometimes contained in literalness, Our Product is at once what it says from everyone’s viewpoint, as long as they are human, but also, from the viewpoint of its producers, the one which is presented on the occasion of the launch event that the biennial is. It is in fact possible to talk here about producers, because, for the occasion, Pamela Rosenkranz has surrounded herself with specialists in various domains for its design, including the perfumers Dominique Ropion and Frédéric Malle, and the philosopher Robin Mackay… The “product strategy” is extremely thorough, even extending to the diffusion of hormones and bacteria in the pavilion’s ventilation system, in order to optimize its reception.

There is a tendency to think, at first glance, that the usefulness of words is to make reality more intelligible. However, and in particular since the end of the 1950s and the first forays of marketing in the day-to-day life of those henceforth known as “targets”, words can also, on the contrary, be used for the purpose of obscuring that same reality, especially in the sectors of technology and cosmetics (we shall refrain, here, from broaching the political arena, which would remove us just a tad from our subject, even though it offers plenty of adequate examples). The abundance of technical and scientific terms in the advertising discourse—the AHAs, the coenzyme Q10, micelles, the molecule MG6P “source of pre-activate bio-energy which boosts the natural synthesis of collagen and elastine”,7 but also the Smartphones “CPU Quad-Core, 1.9 GHz with its Super AMOLED screen, 1920 x 1080 (FHD), with a resolution of 13 MP8”—gives consumers a sensation of security: the less they understand the terms used to describe the product, the more reliable it seems, because at the cutting edge of technology. While at the same time permitting the company to take advantage of a “transparent” communication as far as the composition of its products is concerned, this emphasis on terms which do not pertain to ordinary language is also a way of drowning the individual in information—information which, in the end of the day, he does not need. And even though people enjoy appropriating learned words and, as the anthropologist Eric Chauvier describes it, “we have entered the age of specialist language for one and all”,9 the meaning very often remains obscure. The Greek nomothete retrained into “naming”, and henceforth launching a product is, above all else, launching its name. The tendency towards the greatest possible compatibility between name and thing, by using the technical features of a product to describe it—a “plasma” screen, a “micellar” make-up removing water—, lays a varnish of “truth” over the object.

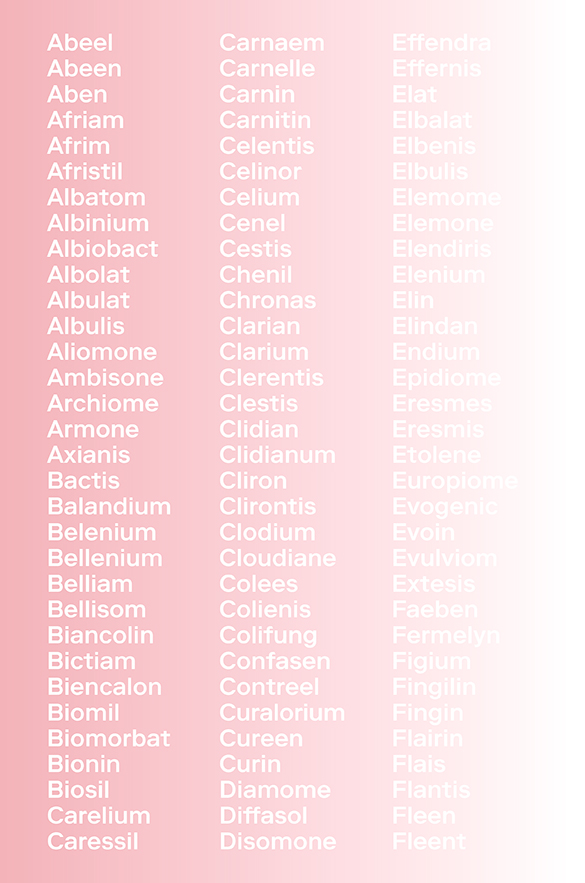

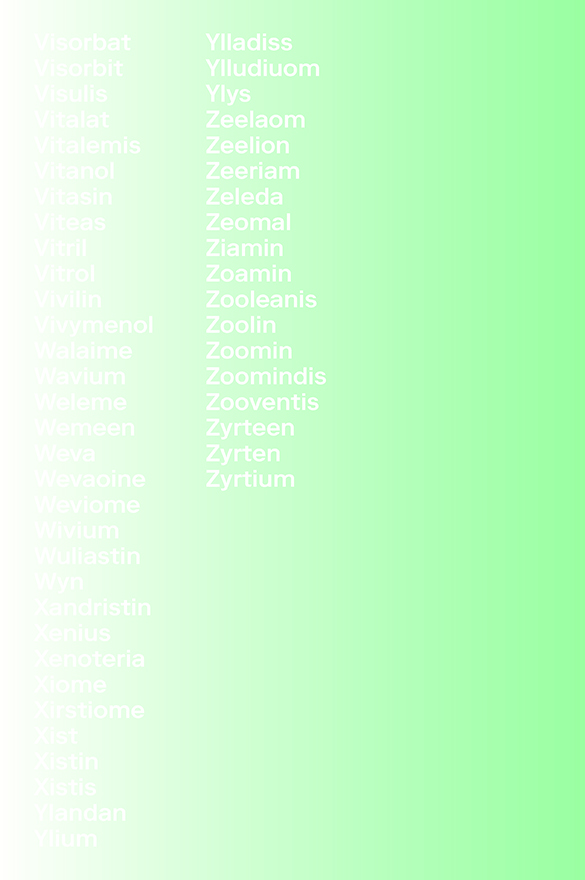

Page from the booklet published on the occasion of Our Product at the Pavilion of Switzerland at the 56th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia 2015. Design : NORM, Zurich.

A booklet10 accompanies Our Product. Its eighteen pages offer a detailed description of the components supposed to form Our Product. From a very lengthy list of terms sounding scientific and pharmaceutical, which opens and ends the document, eighteen are thus excerpted: Neotene, Evoin, Bionin, Umbrotene, Albulis, Solood, Bactis, Refleine, Isolon, Necrion, Elemone, Imersa, Selentis, Vertinel, Holeana, Rilin, Carnaem and Melisone. Descriptions ranging from the extremely plausible —“Burn off the surplus. Rilin is an agent that defies description. It fights for us relentlessly, banishing aggressors, purging the volatile organic compounds that impede natural flow, and restoring our biome. A watchful sentinel, its active sequestering agents constantly fend off a broad range of bioaccumulative toxins. Maximum protection for optimal progress” — to the extremely nebulous (nevertheless calling to mind perfume advertisements) — “Melisone feels as intimate as your own name ; or another, secret name for something even closer to you, a radiant name that can only be whispered. It’s in all of us, this is our firm belief, but sometimes we just need to hear that sound. You might call it a miracle” — by way of the extremely disturbing — “Carnaem is a benediction distilled from the deepest rootstock of human life. Isotonic to the rich serum of progenitor hemoglobin that repairs and restructures, it is the only choice for the cultivation of vitality. Like drinking our own blood from another time, uncompromised by the twenty-first century, to absorb it is to become it. A surge of aerating potency welling up in the core” — follow one another, developing a relatively vague definition of the product. They seem to be striving to contain an idea rather than an object, a sort of disembodied vital function, though endowed with a colour that is at once transparent and radiant.

“surface goes deeper than we think”

“relieving us of the chemical burden of our existence”

“delivering boundless possibilities”

“to bring us back to a world before us”

This biologically anticipatory poetic text, which is both extremely attractive and frightening, written by the artist in collaboration with Robin Mackay, quite simply evokes life, but at its best. Its promises of an ideal of purity and progress result from arguments which surround our everyday lives, be they to do with publicity, medicine and health, politics or religion… In them we find snippets of slogans which have worked their way into our memory—in particular the one about Fiji mineral water which will remind those who managed to see “Our Sun” of the small bottle of that same brand filled with flesh-coloured silicon (Firm Being, 2009), which, together with several others, staked out the space of that exhibition—, a few truisms like “ because we are the sum of the materials that make us – and more”, an at times simplistic ecological sentiment, an undisguised religiosity — “we all rise in the same direction”, “to absorb it is to become”, “you might call it a miracle”. It is possibly also what sticks in our mind at the end of a day, exposed as we are to the linguistic whole which is henceforth our shared lot.

What, when all is said and done, is the product? A kind of materialized human essence, a liquid being which summons both the Panthalassa of the Palaeozoic and genetic manipulations to come. And invariably this same question which remains, beyond the depth of time: is there a trans-linguistic reality or, otherwise put, does what we understand by “the world” exist without a subject to name it?

SOCRATES

But would you say, Hermogenes, that the things differ as the names differ? And are they relative to individuals, as Protagoras tells us? For he says that man is the measure of all things, and that things are to me as they appear to me, and that they are to you as they appear to you. Do you agree with him, or would you say that things have a permanent essence of their own? 11

1 From 30 Oct. 2009 to 6 March 2010, Istituto Svizzero di Roma, Campo S. Agnese, Venice.

2 Salvatore Lacagnina, “The Courage of the Surface”, in Our Sun, catalogue for the exhibition of the same name, Mousse Publishing, p.83-85 : “The thick weft of meanings, the tangle, it was said, of reverberations that links one work to the other, would require thorough descriptions, that involve politics it was said, philosophy, but also the history of the image (each work seems to consciously reactivate artistic languages from the recent past). But it is precisely in the freedom and ambiguity of the surface, if it is true that the content is provisional by definition, that the system activated by Pamela Rosenkranz finds its visual and cognitive completion.”

3 Swiss pavilion, 56th Venice Biennale, from 6 May to 22 November 2015.

4 Cf. Aude Launay, “Of Paint and Men: Jason Loebs, Pamela Rosenkranz, Cheyney Thompson” in 02 n°71, autumn 2014, p. 30 and, for a more in-depth approach, Robin Mackay, “No Core Dump”, in Pamela Rosenkranz, No Core, JRP Ringier, 2012, p. 45-53.

5 John Dewey, Art as Experience, “The Live Creature” (1934) in The Later Works of John Dewey, 1925-1953, Volume 10: 1934, Art as Experience, Southern Illinois University, 1987-2008, p. 19.

6 Rirkrit Tiravanija, “Une rétrospective, (Tomorrow is another fine day)”, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris / ARC, from 10 February to 20 March 2005.

7 Excerpt from a publicity announcement which appeared in ELLE, French edition, 27 March 2015, p. 167.

8 Description of the Samsung Galaxy S4 available on the brand’s website.

9 Éric Chauvier, Les mots sans les choses, Allia, 2014, p. 9. This essay does not deal with the appropriation by the people of a vocabulary coming from the world of advertising, but one hailing rather from the human sciences, i.e. focusing on a usage in current conversation of terms meant to cover concepts which those speaking do not really master, for example those used in psychoanalysis, such as “hysterical” or “ paranoid”, or in sociology, such as “the religious fact”.

10 Available at www.ourproduct.net

11 Plato, Cratylus, in The collected Dialogues, Princeton University Press, 1961, translated by Benjamin Jowett, p.424.

Page from the booklet published on the occasion of Our Product at the Pavilion of Switzerland at the 56th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia 2015. Design : NORM, Zurich.