in conversation with Aude Launay

« If you’ve got something you can’t show, the language has to reflect that » says the actor who plays Omer Fast in his film Everything That Rises Must Converge. This sentence may well uncover the essence of the artist’s work, we discussed it with him.

Your films and the texts that underpin them are much ‘written’ but, at the same time, structured, in your own words, “so that they can be accessible at any time”.1 Was it to open your work to this kind of freedom that you chose art above cinema?

I never made a choice between art and cinema. I never studied cinema and still don’t really think of myself as a filmmaker. I was accepted into graduate school as a painter but had lost interest and stopped painting well before starting my studies. Without a medium, I simply drifted along for a few semesters, tried sculpture, installation and performance and finally ended up in video just as time was up and I had to graduate. And while these experiments in school were short-lived and pretty dreadful, they were all connected by an interest in narrative. This interest sustained me past my studies and into my first works as an artist. For example, CNN Concatenated (2002), which I started working on in 2000 soon after graduating, is primarily a text piece about television. There’s nothing cinematic about it. For the next several years, I thought much more about language and narrative in the context of television and made works for monitors. If cinema existed in the work, it was as a reference and ready-made source of footage still in the context of television. For example, in T3-AEON (2000), I dubbed little voice-over clips onto videocassettes of films in New York area video stores and returned them for others to see. So the idea had much more to do with how we consume films privately, at home and on TV, and with surreptitiously inserting an artwork into circulation in a rental market, than with cinema per se. It was only after working through different options for using found footage that I started developing an interest in shooting the footage myself.

Is your interest in language and narrative something you could define as ‘spontaneous’, at least at the beginning of your practice, or did it come up from some theories you might have been interested in?

As an artist, I have to follow my instincts, whatever they are. Theory mostly provides a framework for understanding something after the fact. There have been exceptions: Dean MacCannell’s book The Tourist, for example, was very helpful for me in defining an approach to sites which can be seen as both historical and performative. This was an interest that took me to the living-history museum of Colonial Williamsburg, where costumed interpreters meet visitors and speak with them as eighteenth-century characters. Fiction is more of an immediate resource. When I get stuck, I try to read my way out of the problem. I just finished re-reading Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49. It’s a wonderful guide for the perplexed and marooned.

Video HD, 77’. Courtesy Omer Fast.

And, as these narratives you produce are all based on some existing narratives, be they stories told to you by people you meet on purpose or real events transmitted by the news —such as Mouammar Khadafi’s death—, does it make you a storyteller? By this I mean what is your position toward (your) authorship?

The exhibition at the Jeu de Paume neatly frames my dysfunctional relationship to narrative and authorship: CNN Concatenated, the earliest work we are showing, is a highly personal yet completely fictional monologue composed entirely from bits of found footage collected from over two years of watching TV. A Tank Translated (2002) presents portraits of Israeli soldiers whose subtitled speech continuously mutates on screen, giving both a faithful translation of the original Hebrew as well as alternative statements that shoot off in different directions and speak a lot about a crisis of meaning. 5000 Feet is the Best (2011) threads together original interview footage with a US drone operator with stylized reenactments of the same interview, including flashback episodes based on material which I wasn’t able or allowed to use. And, finally, the centerpiece of the exhibition, Continuity (Diptych) (2012-15), is a completely fictional feature-length family melodrama about loss and longing, with some moments of horror, surrealism and incest thrown in. I suppose if there’s a way to characterize my position towards authorship it would be erratic and skeptical but constantly trying.

As you mention A Tank Translated, I’d like to ask you to go more thoroughly into the “word processing” technique you employed in this series of videos. The four films broadcast interviews that you conducted with members of an Israeli army tank crew but their speeches appear visibly modified in the subtitles, in a different way for each one, be it by erasing, intertwining, exchanging words… Subtitles are usually seen as a second-rate form of text that we read but only to a certain extent, in any event without paying any attention to its intrinsic textual qualities—of which it is most often devoid. Here, as in Spielberg List (2003, not shown at the Jeu de Paume), they stand as the core of the films. Can you explain this precedence of the text over the images, in the form of a video, and the ways you perform it?

The subjects in all of my works share a kind of liminal condition or status. Soldiers, migrants, adult film performers and funeral directors are all liminal figures in that they cross borders, trespassing into spheres which are off-limits, tabboo, hidden or invisible. I keep returning to these subjects because their liminal status can say a lot about both normative social space as we conceive it, as well as an alternative or disrupted ordering of that space. For me, subtitles exhibit a similar liminal function. You’re right to point out that subtitles are often regarded as second-rate or degraded and I believe that has a lot to do with their in-betweenness. (They temporarily invade the image, disrupting its purity with textual content that serves both as an interpretative bridge and a reminder of its/our inherent foreignness…) In A Tank Translated, I was trying to foreground this liminal function of the text, to find an analogue for what these soldiers represent, especially given their working environment: If anything, the tank is a machine purpose-built to allow its personnel to forcefully cross into a space and disrupt it. It is a thick membrane, a protective ectoplasm which is nevertheless riddled with special holes designed for peeping out but not peering in, and of course for shooting but not being shot at. The subtitles in the work enact a similar liminal operation between transparency and opacity, voyeurism and violence, in that they both protect and reveal its subjects, punching holes in their sentences or adding layers and layers of contesting meanings. It’s never exactly clear who’s inside and who’s outside of the text and this state of permanent in-betweenness obviously has a lot to do with the work’s political subject matter, i.e a state whose own borders are undefined and whose operations are highly contested.

(Driver, detail). 4 silent videos, 9’30, 4’09, 13’25, 5’01. Courtesy Omer Fast.

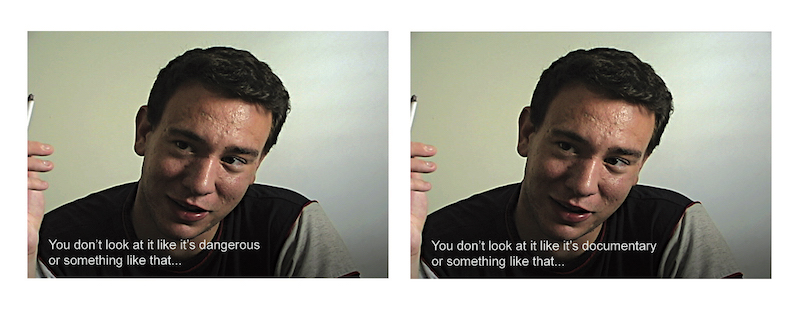

In many of your films, eventually, either images don’t ‘show’ that much (as it turns to be in A Tank Translated), either they appear to be contradicted by the text they are associated with, be it a voice-over, subtitles, or, in a more indirect way, from inside the very narrative told by some of the film characters—as it happens in Continuity (Diptych) when Niklas, one of the Daniels, mentions a woman working at the bakery with Katja retorting that no woman works there and as, effectively, we are only presented with men in the bakery scenes, or in 5000 Feet is the Best with the embedded story of the man obsessed with trains who hijacks one some day and spends that day driving it as a real train driver and who we see as a black man until the interviewer asks the so-called drone pilot telling the story: “so why does the guy have to be black?” and that the pilot answers : “I didn’t say he was black. Did anyone mention color?”, and then the man on the image suddenly turns into a white man.

In Her Face was covered (part II) (2011), the image even seems at times to disobey the text (e.g., when a sandy islet covered with palm trees shows up following the sentence “There were people nearby” which it was supposed to ‘illustrate’) disrupting the outward seriousness of the film by absurd humorous flashes.

At times, there are images themselves that contradict each other in a somewhat subtle way—like when the blonde actress in Everything That Rises Must Converge (2013) dips her hair in her bath and then gets out of the bathtub with her hair dry. Is the whole of your works an undermining of the image as immediate and violent it can be—violent in the sense of Roland Barthes writing, about photography, “violent: not because it shows violent things, but because on each occasion it fills the sight by force”3?

I understand what Barthes has to say about the image as a corollary to the old Platonic allergory of the cave, wherein the violence inherent in an image derives from the sensory challenge it represents and the fetishistic power we attach to it. My grandmother used a small pair of scissors to methodically cut out her face from every single picture she had. The violence she exacted on a lifetime of photos must be seen as compensatory to the violence she must have felt these images had done to her. So when we rip apart or delete photos that are unflattering, we try to remove inconsistencies from the visual record in order to maintain a more consistent sense of self: Either the unflattering image exists or my more flattering self-perception, but not both. Even if we’re not prone to manifestly neurotic outbursts like my dear grandmother, we constantly compile and edit images that are very often chaotic and contradictory in order to produce a narrative that is consistent. No news here. This is how reality is constructed. Following this logic, the visual inconsistencies that you find in my work are manifestations of this dynamic, they’re like little Brechtian ticks meant as reminders or corrections.

The type of repetition you use in 5000 Feet is the Best (30 minutes long) and in Continuity (78 minutes long for the Dyptich version) is a very particular one —at first sight it seems that we’re facing a looped video and that the first scene we saw is starting again— it’s a repetition which enables slight differences to occur. It’s more sublte in 5000 Feet as, in Continuity, the difference is made obvious by the change of actor embodying Daniel, the son of the couple but, anyway, it sets up a somewhat mysterious temporality, non-linear, that frees the narratives from causal relations and, in that way, from a rigid teleology. There is no progress at work in these narratives, much more a coexistence than a succession of the stories, which implies that the ‘new’ story we’re presented with doesn’t necessarily replace the ‘former’ one, and that there is no hierarchy that prevails over the different narratives. Yet in an interview4 you named yourself a “boring materialist” who believes “time is unbending and linear”…

It should be evident by now that I’m a pathological liar. Lying makes life more interesting and it’s certainly the foundation of all true art. In any case, the private views I hold as a person are not necessarily the ones I’m interested in exploring in my work. In Continuity there is a whole nexus of causal relations at play, but they are mostly hinted at and are largely submerged with only the symptoms showing. For example, the parents’ recurring interactions with various young men are implicitly connected to a loss they’ve experienced (either the tragic loss of a son or the more mundane but still very painful loss of mojo in their married life…). The loss is the big bang that sets up a chain reaction that we must puzzle through as viewers. And since there’s lots of exertion and no happy end – nor a sad one for that matter – we are left with what I hope is a stronger sense of the shared temporality that binds this strange couple together – literally the passage of time as experienced by two persons in crisis. Seen in this way, the various theatrical engagements with young men which repeat in the story are attempts at therapy by a couple whose linear lives have been violently disrupted. And I think this is what I’m really trying to get at: If we follow Lacan’s notion that the traumatized subject is characterized by a breakdown in signification, then what emerges from this rupture are the physical and temporal in their inchoate, unassimilable, eternal states. Of course there’s lots of talking being done as part of the therapy. But as you rightly point out, there are no fixed or stable coordinates: No before and after, no original and copy, no better or worse, no beginning or ending. As the husband confesses to one of the young men he’s about to dispatch: “You know what our secret is? I cook and she cleans. But on weekends we switch places.”

Video HD, 77’. Courtesy Omer Fast.

The most frequent subject matter in your films is war. Except for the fact that, as an Israeli, compared to West European people of your generation, it is of more obvious and direct ‘interest’, so awful it can be to put it this way, is that so overriding because it could be a sort of ultimate subject, encompassing the issues of death and vision which are of prime importance in your work? Does war entail a greater ‘narrative potential’, if I may say, as it is, for the lucky citizens, made in their name without them being in direct contact with it? As it is, for many of us —with the wide Internet spread of the GoPro videos made by the soldiers themselves, the images taken by the drones and broadcasted in the news, etc.—, and including the drone pilots themselves, a mediated relation to death…

I would argue that the main subject in my work is the relationship of the verbal and visual. My work is nothing but an attempt to map this relationship across various contexts. And since death represents the very outer limit where both the verbal and the visual must cease – or be allegorized and reimagined – death becomes a kind of screen subject, the staging ground for a radical alterity. This is about as abstract as I can get. But I’m not an abstract thinker. I need my work to grapple with the issues that preoccupy me, to make them tangible, more specific.

Video HD, 77’. Courtesy Omer Fast.

1 Omer Fast, Present Continous, 2015. Texts by Jennifer Allen, Tom McCarthy, Laurence Sillars, together with an interview with Omer Fast by Marina Vinyes Albes. Published by Jeu de Paume, Paris; Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead and Kunst en Museum of Modern Art, Aalborg, p. 107.

2 Dean MacCannell, The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class, University of California Press, 1976.

3 in Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, 1980. (En. trans. 1982).

4 Cf. Omer Fast, Present Continous, op.cit, p. 110.

Originally published in 02 #76, Winter 2015-16

On the occasion of:

Omer Fast, « Le présent continue », Jeu de Paume, Paris, from 20 October 2015 to 24 January 2016 ;

Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, from 18 March to 26 June 2016 ;

Kunsten Museum of Modern Art, Aalborg, from 23 September 2016 to 8 January 2017.