Review of the exhibitionWATCHED! Surveillance, Art and Photography held at Kunsthal Aarhus & ARoS, Aarhus*, Nov.16– Dec.31.2016 & James Bridle, Apophenia at Galleri Image, Aarhus, Oct.14– Dec.18.2016

While the controversy surrounding the TES, the mega-file of biometric data which will cover the entire French population, consumes the land,1 thus rekindling the general issue about the recording of citizens’data and, more broadly, their surveillance, a travelling show has seen fit to call a spade a spade: “Watched! Surveillance, Art and Photography”, organized by the researcher Louise Wolthers, curator at the Gothenberg-based Hasselblad Foundation. The most impressive of the installations on view, Images of the artifacts used by the main hand (2004, ongoing) by Alberto Frigo, is being presented in the guise of something that is, at first glance, almost humorous, so far-fetched does the project seem, but it is still quite mind-blowing. As its title suggests, it is an exhaustive collection of photographs of each of the objects used every day by the artist’s right hand, already containing some 300,000 images of toothbrushes, screwdrivers, keyboards, telephones, frying pans, forks, biros, etc. Initiated in 2003, i.e. overlapping with the creation of those future colossi of image self-management, LinkedIn and Myspace, and just before the first massive distributors of images depicting the ordinariness of everyone’s daily life, Facebook and Flickr, worthy heir of the British Mass Observation movement, 2 it is scheduled to continue up until 2040, when it will form a square measuring 36 feet by 36, which will contain about a million photos. This monomania is being developed somewhere between a Perec-like poetic inventory and a political refusal of automation, left, right and centre. “Mimicking the very procedure of automation, and physically re-enacting the algorithm of the surveillance apparatus” enable the artist “not to become a part of the machine but rather to act as a machine”, because “a new surveillance infrastructure has created smart machines that take the place of the surveillant, and — more dramatically — of ourselves (the surveilled).”3 Between the fine goal of self-knowledge and the voluntary servitude which is what self-quantification has become (sleep time, glucose level, heartbeat and mood all listed and memorized by our watches, bracelets and telephones), which this promethean quest calls to mind, even if it claims to be quite distinct from it, there is an epistemological break which many of us are still refusing to see. In fact, surveillance does not result solely from an obvious and unilateral imposition, and we often submit to it more readily than it might seem. But the idea behind the exhibition tends in a more general way towards the opposite notion: generalized surveillance, which we might from now on more aptly call multiveillance, is having more and more light shed on it by artists using its own means.

So it goes with this impressive technology of advanced facial recognition which, after photos taken by four different cameras, makes it possible to reconstruct the three-dimensional facsimile of a face without any cooperation from the subject. Much more than a mere ID photo, these portraits, for whose making the person whose portrait it is “is not necessarily aware of the camera”4, are increasingly being used by border police units and in major places of passage in European metropolises. Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin have made use of this technique in Spirit is a Bone (2013) to reproduce the faces of Muscovites (including one of the Pussy Riot girls) invited for the occasion. What makes this technique so fascinating is that, devised for photographing people who are not keen on the idea, it nevertheless produces portraits with the gaze staring at the lens, disarmingly head-on, presaging the worrying facility with which our patterns of behaviour and our very gestures can be mechanically modified without our consent, while it is also possible to see it as a way of bringing out the “truth” which would lend a face its identity,5 in a vision inherited from the pseudo-scientific arguments of phrenology, which strangely informs certain current research in the field of facial recognition.6

If the “(wo)man in the street” is already relatively reluctant to let her/himself be visually recorded, the person who is not officially a “(wo)man in the street”, by dint of not having papers, clearly comes up against even greater difficulties. Four works dealing with this issue form one of the powerful themes of this show.

With Drifting (2014), Hanne Nielsen & Birgit Johnsen play with a mirror effect in the tale they tell—that of a man (an actual fact) found on a raft floating in the international waters between Denmark and Sweden, who refused to reveal his identity to the authorities—by way of a collage intermingling snippets from newspapers and blurred photos, to create a narrative in which anecdote quarrels with suppositions, whereas, in a collection of photos, Marco Poloni unveils the parallel paths used on the island of Lampedusa by the temporary residents called tourists and migrants (Displacement Island, 2006), and, in No Man’s Land (2011), Mishka Henner re-situates views of non-places discovered on Google Earth, in which isolated and scantily clad women appear. Using crosschecked information found in forums associated with prostitution, he captions these screen captures of addresses on these almost deserted roadsides and edges of woods, thus producing a delicate and somewhat unexpected reflection about the cogs of the power of geolocation. As for Tina Enghoff, her Migrant Documents (2013) tell the story of the homeless and undocumented refugees in the parks of the Danish capital, without ever showing their faces, evoking their illicit street life by way of large black and white prints of garbage bags and other effects barely hidden among the branches of trees; a video shot by a surveillance camera during several nights and mornings in one of these parks, alternating non-events and moments when you glimpse these homeless people covering themselves and lying down, then getting up again and stashing their meagre belongings in the bushes; and close-ups of test-tubes containing blood samples from these stateless persons, the only moment when they agree to undergo identification being during the care offered them by a controversial local Red Cross unit. In this regard, Louise Wolthers conjures up a kind of “caring sort of surveillance” in the footsteps of the sociologist Helen Hintjens who, for her part, puts forward theories about selective non-surveillance: in a nutshell, persons deemed undesirable in a country are subject to a twofold surveillance system, the first, an intense one, near borders in particular, administrated by the executive branch, and the second, on the other hand, tending towards it own denial. With extreme vigilance then making way for a total absence of considerateness, those who have no rights very often do not even have the right to be noticed. For Tina Enghoff, photography is above all a matter of cooperating with your subjects: it must not be content with the rhetorical role in which it is being increasingly confined; rather it must show efficiency.

Almost all the works on view in this chapter of Watched! at the Aarhus Kunsthal share in common this underlying question to do with the nature of identity (is it restricted to purely physical features: blood group, distance between the eyes, possessions, address, documents, etc?), undoubtedly linked to the issue of control (of oneself, of society, etc.), and, thereby, of the public place (can the word public be applied to the place where it is authorized to record us without our consent? and the word private to the place in which we consent to submit to being recorded?) The most disturbing work is perhaps James Bridle’s Homo Sacer (2014), incarnating in one of those synthetic holograms-cum-greeters basic phrases in definitions of nationality and citizenship based on British and international laws, as well as certain Theresa May (then Home Secretary) quotations, moving from a friendly “you have a right to a nationality” to darker pronouncements like:“The state may retain the right to deprive you of your nationality if you have conducted yourself in a manner prejudicial to the vital interests of the state”, and culminating in the following conclusion: “Citizenship is a privilege, not a right”. A little further on, in the heart of its monumental staircase, the imposing ARoS museum is projecting Seamless Transitions (2015), an animated film made by the selfsame James Bridle, which is just as disturbing. Presenting 3D models of a detention centre, an in-camera courtroom of the special commission for appeals by the British immigration department, and the special area reserved for private jets at Stansted airport, from where persons being deported from Britain are “sent home”, produced in the wake of a thorough investigation of the artist, because it is formally prohibited to photograph these places, the video loop is in this respect striking insomuch as it is perfectly aware of the artificiality of the images it shows: everything is far too clean, polished and hushed, as glorious as an advertisement for a luxurious loft complex pre-sale, turning against itself that imagery of places which will never really exist as such.

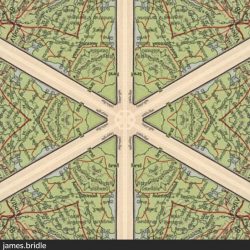

Lastly, the historic Galleri Image offers the artist its premises for a small retrospective show of his pieces using surveillance tools to produce abstractions. Whether he changes live video flows of New York cctv cameras (Rorschcams, 2014), views of London taken by a military surveillance balloon (Anicon, 2014), or Google Maps overflights (Rorschmaps, from 2011 on) into kaleidoscopic images, the aestheticization of the results of these surveillance methods seems to render them null and void, but also dangerously fun.

This feeling is happily countered by Diorama (for Louis Daguerre) (2016): considering the very first photograph of a human being as possibly stemming from surveillance, because taken unbeknownst to that man (although this latter’s presence in the image is thoroughly accidental), Bridle pays a subtle tribute to him by filming the Place de la République in Paris (precisely where Daguerre had his studio) and gradually emptying his images of their occupants with the help of artificial vision programmes: reversing both the procedure of the photographic pioneer and the use for which these tools have been created, he deletes from the image all those who are in them, again unwittingly, rightly reminding us that the “surveillance culture is not a product of technological determination”.7

1 This file, a development of the one regrouping the data to do with already published biometric passports (i.e. concerning some 17 million people) and with “almost the entire French population” to use the CNIL’s words, “which we should remember owes its creation precisely to the (virulent) protests of many citizens against the creation of a file similar to the TES file in 1974, the SAFARI file” (https://www.laquadrature.net/fr/oln-fichier-tes-danger-pour-libertes), that is, a file containing a photo of the subject’s face, finger-prints, civil status, identity, filiation, and each citizen’s physical and digital addresses, is in the process of being set up without any direct consultation with the population and without any defined restriction of its future uses.

2 Cf. Pablo Abend & Mathias Fuchs, “The Quantified Self and Statistical Bodies”, in Digital Culture & Society, transcript, 2016, vol.2, issue 1, p. 6-7.

3 Alberto Frigo, “Living up to the Surveillance Algorithm”, in WATCHED! Surveillance, Art and Photography, p. 252, 255 et 251.

4 “The Bone Cannot Lie”, a conversation between Eyal Weizman and Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin, in Spirit is a Bone, MACK, 2015, p. 207.

5 “The documentary sculpture returns us back to the skull, and the ‘truth’ underneath the face.”, Eyal Weizman, Spirit is a Bone, op. cit., p. 237.

6 https://arxiv.org/abs/1611.04135 (for example).

7 Quote from an interview with the artist, to be published on www.zerodeux.fr/en

* Curated by: Louise Wolthers, Dragana Vujanovic, Niclas Östlind. With: Jason E. Bowman, James Bridle, Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin, Tina Enghoff, Alberto Frigo, Charlotte Haslund-Christensen, Mishka Henner, Hanne Nielsen & Birgit Johnsen, Marco Poloni, Meriç Algún Ringborg, Ann-Sofi Sidén, Hito Steyerl.

WATCHED! Surveillance, Art and Photography, Hasselblad Foundation, C/O Berlin, Galleri Image, Kunsthal Aarhus, Valand Academy, 2016, Walther König, 296 pages.